Talk of a “K-shaped” economy is trending again.

The term first gained momentum in 2020, when the pandemic exposed how unevenly American prosperity was distributed. Today, with spending power even more concentrated at the top, economists warn that the US economy is becoming dangerously top-heavy.

For many Americans, the economy looks strong on paper, but feels fragile in daily life. Jobs are less secure, while big ticket items like housing are much more expensive. One image captures the risk well: a Jenga tower. From afar, a Jenga tower economy looks impressive, rising quarter after quarter. But look closely at the base, and you see blocks being pulled out and stacked on top. So the taller the tower grows, the less stable it becomes.

Recent data reflects this. GDP growth in Q2 was the fastest in nearly two years. “The US will finish the year with 3% real GDP growth, despite the lengthy government shutdown,” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent bragged in an interview with CBS. But the Fed’s latest 25 basis point rate cut, prompted by weakening labor-market data, suggests that things are unstable below the surface. A big chunk of the growth was driven by large tech players like Nvidia, and consumer spending was fuelled by high income consumers.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, warns that such concentrated spending power creates a single point of failure. “It makes the economy very vulnerable, if anything goes off the rails for these high-income, high-net-worth households.”

This has now become a political issue. "Affordability" dominated campaign messaging in recent elections, helping Democrats win easily in New York City, New Jersey, and Virginia. Voters are not looking at GDP charts. They are looking at grocery bills, rent hikes and job insecurity.

So how long can a top-heavy economy can keep rising before the tower starts to wobble?

The top 10% now drive consumer spending

Companies have been watching this income divide play out. Kroger noted in September that low and middle-income shoppers are relying more on coupons, switching to store brands, and cutting back on dining out. Procter & Gamble reported a similar pattern in their data: households living paycheck to paycheck are chasing discounts, while affluent consumers continue to buy in bulk without hesitation.

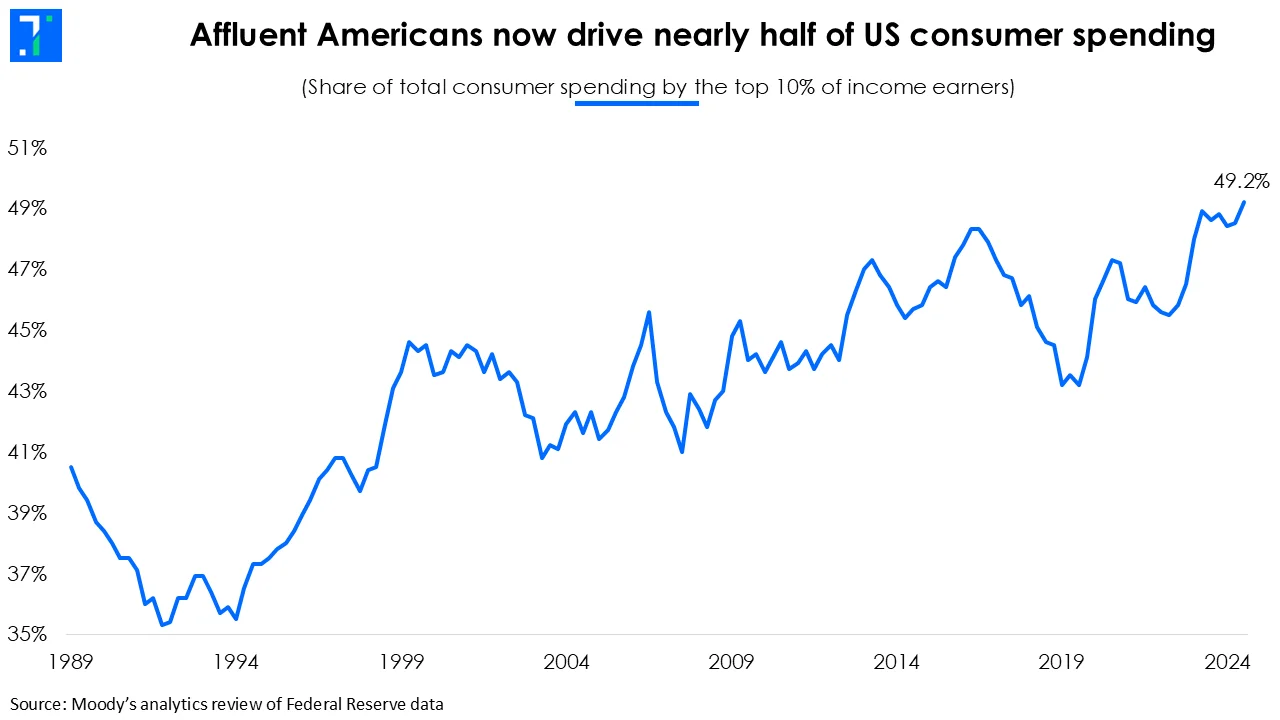

High-income Americans, the top 10%, now account for about half of all US consumer spending. In the early 1990s, that figure was closer to one-third.

This imbalance has been decades in the making. These wealthier households, supported by rising stock portfolios and higher home values, are spending freely. Lower-income consumers are pulling back as inflation eats away at purchasing power, and a cooling job market leaves them exposed.

Over the past year, food prices rose 3.1%. Energy costs increased 2.8%, with natural gas up 11.7% and electricity up 5.1%. Shelter costs climbed 3.6%, and medical care rose 3.3%.

As a result, more Americans are slipping into the lower leg of the “K,” and are struggling to keep up with basic expenses.

As this divide deepens, Gen Z is responding differently. Unlike earlier generations that usually waited until their 30s to invest, many young adults are entering stock markets early. Easy-to-use trading apps, greater access to financial education, and the need to build wealth outside traditional career paths are driving the shift. Surveys show a growing share of Gen Z investing before age 25, as their wages lag behind rising asset prices.

The labor market is flashing warning signs

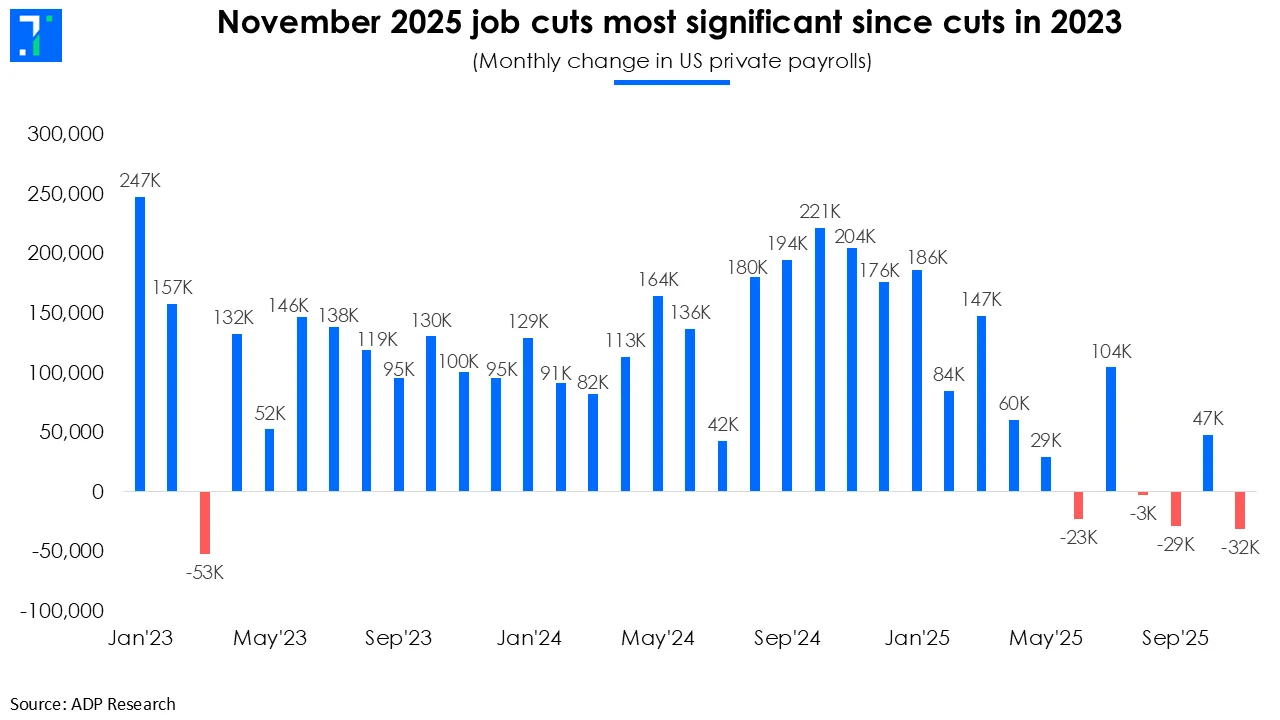

Fresh labor data reinforces the strain consumers are talking about. ADP data shows that private employers shed 32,000 jobs in November, far below expectations for a gain of 40,000. The losses were broad-based, but small businesses were hit hardest. Firms with fewer than 50 employees cut 120,000 jobs, reflecting limited ability to absorb higher costs tied to inflation, utilities, and tariffs.

Job openings in October remained elevated at about 7.7 million but showed little change from the previous month. Layoffs rose to their highest level in nearly three years, while the share of workers quitting voluntarily declined. The drop in voluntary quits suggests growing uncertainty about finding better opportunities.

Wage trends also point to cooling momentum. Pay and benefits are rising more slowly. While compensation gains still exceed inflation, the gap is becoming smaller, which means that employers now have more power in negotiating wages.

This leaves the Fed in a difficult position. Growth and unemployment look stable on the surface, but policymakers have delivered a third rate cut as signs of weakness accumulate, particularly in white-collar jobs. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has cautioned that employment data may be "overstating the numbers", with internal estimates suggesting monthly job gains could be inflated by as much as 60,000.

Consumer sentiment has held up

Despite these pressures, parts of the economy are showing more strength than expected. High-end spending is strong, and real-time card data says that demand is holding up among wealthier consumers.

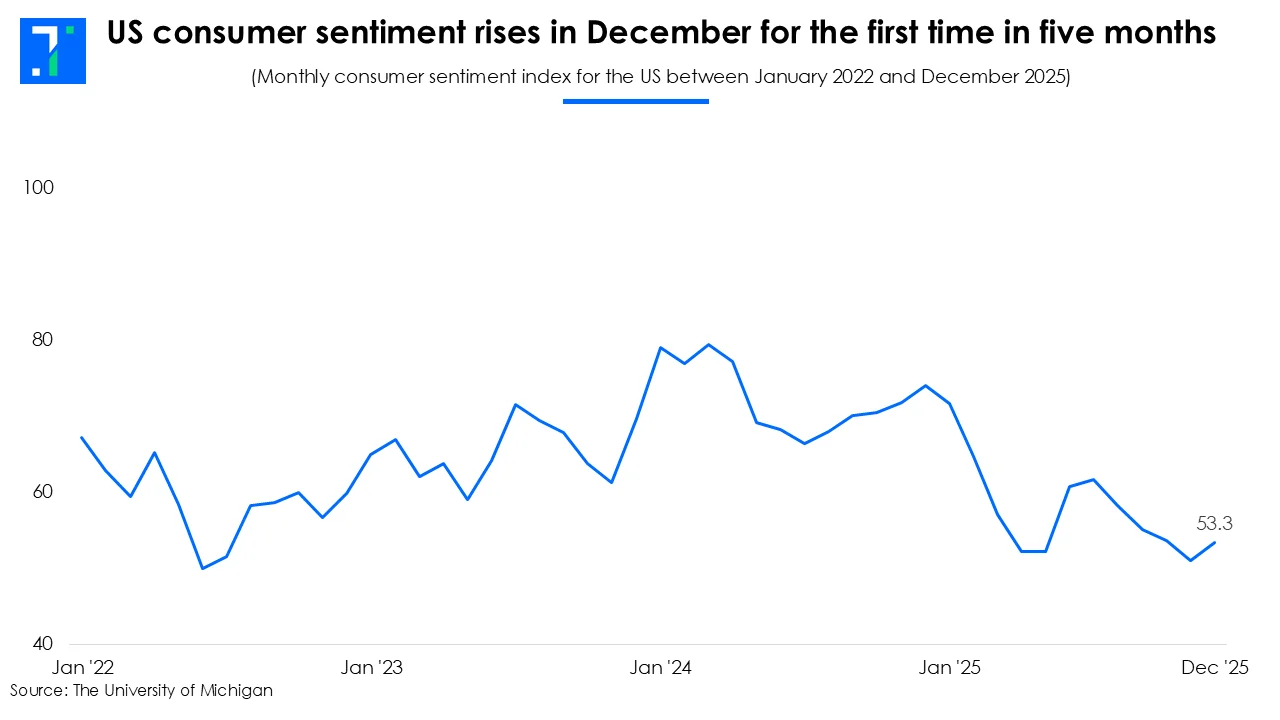

US consumer sentiment rose in December for the first time in five months. The University of Michigan’s preliminary sentiment index climbed to 53.3, up from 51 in November, as inflation expectations eased. Surveys conducted later in November captured a rebound in confidence following the end of the government shutdown, which had weighed on household mood.

Corporate earnings tell a similar story. Retailers who focused on shoppers with fat wallets, are outperforming. Macy’s CEO Tony Spring noted that Bloomingdale’s posted 9% year-over-year sales growth in Q3, driven by consumers willing to spend.

The holiday season reinforced this trend. Adobe Analytics data showed record online sales of $11.8 billion on Black Friday, up more than 9% from last year. Cyber Monday sales reached $14.3 billion, a 7.1% increase.

Shoppers gravitated toward electronics, apparel, and home goods. But they were also often using buy-now-pay-later options to stretch budgets.

Will the tower keep rising?

Looking ahead, the main risk lies with high-income consumers, who now drive much of the overall demand. Their confidence depends heavily on rising stock prices. Strong gains in the S&P 500 boost household wealth and encourage spending, but that support remains fragile. Economists at Oxford Economics note that moves in stocks and other financial assets now shape how consumers view their own future and how much they spend. If overheated tech stocks cool, or markets turn volatile, spending can slow down fast.

The economy still looks strong from a distance, and for many at the top, it genuinely is. But strength built on concentration is brittle. As spending power narrows, the tower grows taller and the margin for error shrinks. The end of a Jenga game rarely comes with a warning. A tower can rise for a long time before gravity reasserts itself.